There soon may be far fewer males around. At least in the oceans.

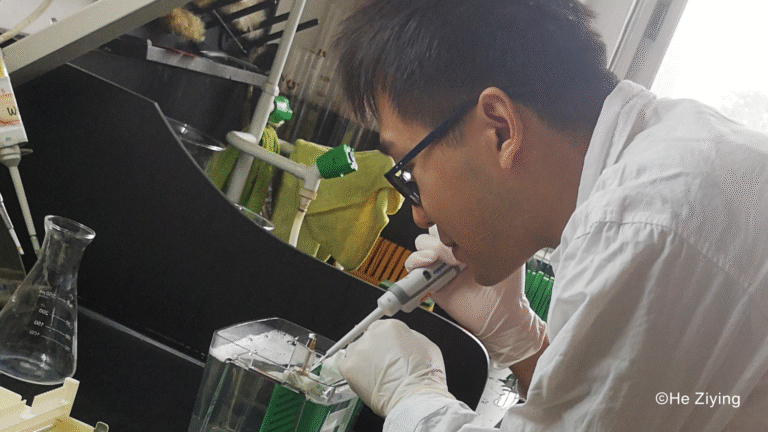

One of the consequences of global climate change is ocean acidification. HKU postdoctoral researcher Dr Xin Dang, who works in Integrative Biology and Evolutionary Ecology Research Lab (iBEERLab) at the School of Biological Sciences and the Swire Institute of Marine Science (SWIMS), discovered that high acidity can have a potentially catastrophic effect on oysters – the near-disappearance of males.

Research on environmental sex determination (ESD) shows that the sex of the offspring of certain species can be decided by an environmental factor, such as temperature. For example, a crocodile egg will develop into a female if the temperatures at a certain period of its development are below a threshold, and into a male if they are higher.

While most of the research on ESD has focussed on the effects of temperature, Dr Dang showed that high acidity in seawater can also influence sex ratios, making oysters produce a lot more females than males. This was a major discovery, and the publication made the cover of the journal Environmental Science and Technology. But Dr Dang had stumbled on the idea accidentally: “I was identifying the sex of oysters for a completely different project, and saw that the sex ratios were very different under different experimental pH (acidity) conditions! I wanted to know more.”

Crucially, he says, the bias towards producing female offspring is inherited in oysters. The females born to a generation of oysters that experienced a high-acidity environment will also produce more female offspring even if they do not experience such an environment themselves. Then, in just a few generations, the proportion of males in a population – for example oysters living in one bay – can be whittled down to a very low percentage. “For example, the first generation is 50% female, the second 70%, the third – more than 90%,” says Dr Dang.

Why is having fewer males around bad?

Female oysters produce eggs which are then fertilised in the water by the sperm made by male oysters. Normally, in a population, eggs will be fertilised by many different males. But, if there are very few males, then the same male will fertilise a very large number of eggs from different females. Put simply – one father, lots of different mothers, and many of the young oysters in the bay are now half-siblings.

Why is being part of one big family a problem? Because the oysters in the bay now have at their disposal far less genetic diversity – in many, half of the genes are now exactly the same, as they come from the same father. But, having variations in the gene pool is vital for living organisms to adapt to environmental challenges and threats.

For example: imagine that a new virus starts attacking the oysters in the bay. It kills many, but some oysters just happen to have versions of the genes that can enable them to resist the virus. These oysters will survive and pass these genes to their offspring. The population lives on. But, if most oysters are genetically very similar, the chances of these useful genes being around are much lower. The population may be unable to adapt to the virus, and oysters will go extinct in the bay.

The mechanism behind acidity producing more females in oysters is still not known, says Dr Dang, adding that he will focus on researching this in the near future. One hypothesis, he says, is that acidic pH deactivates the genes responsible for the formation of male reproductive organs while promoting those that code for the female ones.

Worryingly, he suspects that acidity-induced sex determination may not be limited to oysters, but could be present in other bivalve molluscs that are related to oysters, such as mussels and clams. Rising atmospheric carbon dioxide, and resulting higher acidity of the seawater, may distort their sex ratios, causing populations of bivalves to crash and go locally extinct.

This may have very far reaching effects on both ecosystems and people, says Dr Dang: “Bivalves are fundamental species for marine ecosystems. They are reef building animals, and these reefs provide shelter for many species of marine life. Bivalves also filter the water and contribute to the stabilisation of shores. Moreover, they are food for both marine animals and humans. We cannot imagine a coastal ecosystem without bivalves.”

This project was a collaboration between the iBEERLab led by Professor Juan Diego Gaitán-Espitia and the research group led by Professor Vengatesen Thiyagarajan who provided the facilities to grow the oysters. The oysters were sourced from commercial oyster hatcheries in the Chinese Mainland.

The hardest part of this project was to get multiple generations of oysters, says Dr Dang: “To get one generation, you have to wait for a year, so it took three years to get results and publish the paper.” But it was worth the time and effort, he says: “We hope that our paper brings more researchers together, to work and collaborate on this very important topic.”